DISCLAIMER: THIS GUIDE DOES NOT TELL YOU WHAT INVESTMENT PRODUCT YOU SHOULD BUY. IT AIMS TO TEACH YOU ABOUT INVESTING SO THAT YOU CAN MAKE DECISIONS FOR YOURSELF. If you just want to know what to buy without all the learning, the best I can do is to point you to a robo-advisor like Endowus (I am not familiar with others, and please only use their Flagship portfolio). I would also highly recommend seeking out a fee-only advisor, i.e. an advisor that does not get paid by being commissioned to sell you products. All the best!

The basic idea behind investing is simple: buy a product for $X, sell it at a later time for $X+your investment returns. Yet the world of investing is needlessly complex. Your friends, family, and colleagues often talk about how they invest in gold, crypto, real estate, bonds, ETFs, or whatever the new shiny toy is. Or perhaps they do day trading, pick stocks, and trade options. You have some idea of what some of these investments are but have no confidence in entering this complex world. You think that you will get burnt badly if you just buy an investment haphazardly, so you (very reasonably) push the idea of investing aside entirely or only invest when guided by a professional hand.

Unfortunately, doing both of these things can severely hinder your financial goals. For one, it is easy to underestimate future spending. It is not easy to get a sense of how much money you actually need without some careful planning. As for the other, there are sometimes serious conflicts of interest coming into play when professionals sell you investment products. They may earn a bigger commission by selling you products that have high annual fees, or sell you products with relatively low returns, or both. It is even possible that they have your best interests at heart, but are simply unaware of better products.

I hope to convince you that (1) learning about investing is important, (2) investing can be simple, sensible, and life-changing, and (3) you should at least take a step towards sensible investing. None of what I say is meant to be investment advice, I only try to explain and demystify products and concepts in the investing world. I aim to give you reasons for and against buying different products, so that you are well-equipped to make your own decision on what works for you. I do not profit from any of the investment products I mention, and I try to give an unbiased view wherever possible.

Here’s what would be covered in this post:

- Why learn about investing?

- What is a stock/bond/ETF/…?

- Is investing important?

- What sensible investing looks like

- Putting everything together

- The end!

Why learn about investing?

An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.

Benjamin Franklin

You might think that there is no need for you to learn to invest, just Google or ChatGPT a basic investment strategy, follow it, and go on your merry way. I am actually very sympathetic to this. I wish investing could be as simple as buying a phone online, receiving it the next day, and getting what you paid for in full working condition. But this is not how investment often works. There are a few big hindrances to getting good results from investing:

- Buying the wrong product

- Not being able to get reliable advice

- Being given the responsibility to trade

Buying the wrong product. Without having basic investing knowledge, it is often easy to buy into a charismatic sales pitch or an online personality who tells you this investment is the best thing in the world. Even when the investment is sensible, learning how to invest helps you to make an informed decision for what is best for your own needs, preferences, and risk appetite, which is unique from everyone else.

Not being able to get reliable advice. Due to both conflicts of interests and sometimes just being uninformed, financial advice can sometimes be unreliable. Being informed about investing is helpful even if you plan to seek a professional for advice. It allows you to single out the ones that are both well-informed and have your best interests at heart.

Being given the responsibility to trade. In reality, most of us do not have access to high-quality financial advice. It bears on us to make at least 2 important trades: buying the product, and selling the product. This is essentially like having a phone delivered to you in parts and asking you to put it together—most laypersons will make a costly mistake at some point. When given the responsibility to trade, you need to know when to sell and when to not sell. It is easy to say you should buy high and sell low, but in reality, it is difficult to follow. Every decline in price comes with a narrative that makes it seem like things will never be the same again. And it is often easy to get sucked into narratives and the negative emotions surrounding it, leading to bad investment decisions.

Learning about investing is perhaps one of the few things in your control that can greatly increase your future investment returns. It helps you to buy better products, find better financial advice, and make better investment decisions. Simply put learning about investing literally increases your expected investment returns. So if you can spare some time today to learn about investing, it might just be the highest dollar-per-hour return you will ever earn.

More broadly, investing is only one part of being more financially literate. I would argue that being financially literate is a required skill for engaging with the world. Just like how reading, writing, and speaking is required to interact with other people; being financially literate is required to interact with the economy, and society more generally. Financial literacy isn’t just about how to make money. It’s about learning how to be happier, more free, and more in control of your life. Since we are often forced to be at the steering wheel of our financial lives, we should learn how to drive. This blog aims to help you bridge the first step to educating yourself and improving your financial literacy.

What is a stock/bond/ETF/…?

There are dozens of products and instruments in the world of investing. Investing can be daunting just because of the “language barrier”, so let’s familiarize ourselves with some common terms:

- Stock: An asset that represents ownership of a part of a company.

- Units of stocks are called shares.

- If you own Apple shares, you are literally a part owner of Apple and are entitled to a portion of its profits. Companies sell shares to raise capital.

- Bond: An asset that represents a loan made by a borrower from an investor.

- Governments or companies can raise capital by taking a loan from investors. They are obligated to pay back the loan (called the principal) after a certain time, as well as regular interest.

- Often also called “fixed-income” due to the borrower paying a fixed interest to the loaner.

- Interest: The charge for borrowing money.

- You can think about this as just the price of money itself.

- Index: A collection of assets (like stocks).

- Indices are commonly used to measure performance in a sector, or the market as a whole.

- For instance, the S&P 500 index is a collection of the top 500 companies in the US. It is commonly used to measure the overall performance of the US stock market.

- Market capitalization: The total value of a company’s shares.

- Calculated by: market price per (issued/buyable) share x number of (issued/buyable) shares

- Capitalization-weighted index (cap-weighted index): An index whose components are weighted according to their market capitalization.

- The S&P 500 index, MSCI World Index, Straits Times Index, are all cap-weighted indices.

- For example, if the US stock market occupies 70% of the total market cap of the global stock market, a global cap-weighted index will consist of 70% US stocks.

- Fund: A pool of money from different contributors used for a certain purpose (like investing).

- Index fund: A fund that aims to mimic an index, often by buying the underlying assets at the same weights.

- Exchange: A place where assets are bought and sold.

- Exchange-traded fund (ETF): A fund that allows for trading shares directly on an exchange.

- If you buy a share of an ETF, it is basically like buying the underlying assets directly (some nuances here but doesn’t matter to us).

- An ETF that tracks an index is an index fund. Commonly used to invest into index funds.

- Mutual fund: A fund that only allows for trading of the shares of the mutual fund company.

- If you buy a share of a mutual fund, it is more like buying the mutual fund company shares rather than buying the underlying assets.

- A mutual fund that tracks an index is also an index fund. Commonly used to invest into index funds/combination of index funds.

- Broker/Brokerage firm: A middleman who connects buyers and sellers to complete transactions.

There’s a lot more, but this will be more than sufficient for understanding most commonly discussed investing concepts. For this post, I will mainly be covering stocks and bonds. These two assets alone already allow you to make some of the best portfolios possible.

It is important to note that when people recommend buying “index funds” they are often referring to total market cap-weighted index funds. This means a fund tracking an index that aims to represent the whole market, weighted by market capitalization. An index fund buying only technology stocks is not representing the whole market, and an equal-weighted index is not cap-weighted.

A general point to note is that stocks are understood as being more risky than bonds, but with higher average returns. This makes intuitive sense, since being a shareholder ensures you fully participate in both the upside and downside of a company, i.e. both when it is super profitable and when it is in the red. On the other hand, a borrower is only obliged to pay the debtor how much they owe and the agreed upon interest. When a company goes bankrupt, creditors (those who hold loans) will be compensated first (if they can compensate), while shareholders are compensated after (typically no compensation). This means you typically should not hold stocks if you need the money in the short term (<5years).

Is investing important?

I think it is not obvious to most people that investing is important. For a long time I thought that investing is an optional activity for people who want to generate excess wealth. I now think I am horribly mistaken. People with heaps of spare cash lying around might be fine even if they don’t invest, but ironically investing can get more important for those who earn less. It allows them to retire peacefully, retire earlier, raise their quality of life, and provide a safety net for their dependents.

To understand why investing is important, we need to cover 3 key concepts:

- Compound interest

- Inflation

- Retirement

Compound interest

Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it…he who doesn’t…pays it.

Albert Einstein

Compound interest is simply interest earned on top of interest. Here is an example:

Suppose you make a $10,000 investment that earns 5% per annum (which is often shortened to 5% p.a.).

| Year | Amount at start of the year | Amount at end of the year | Amount earned that year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $10,000 | $10,500 | $500 |

| 2 | $10,500 | $11,025 | $525 |

| 3 | $11,025 | $11,576 | $576 |

As you can see, the amount earned each year increases even though the investor did not put in extra money. This means that the longer you let an investment compound, the larger the overall return. Given a typical investment lifespan (25-50 years), this effect becomes enormous over the lifetime of an investor. A useful heuristic is the “rule of 72”. The rule tells us how long it takes to double our returns:

Time taken to double = 72 / interest rate

So in our example, it would take 72 / 5 = 14.4 years (approximately) to double our invested money. Considering the typical investment lifespan, it is not surprising to see our investor getting double or even quadruple their invested amount.

Compound interest sounds good and all, but if things are this good why isn’t everyone rich? Just throw some money into an investment, let it compound, and everyone can be a millionaire, right? Not so fast. Compound interest is pretty great, but sadly math works equally well in both the positive and negative directions. As it turns out, the negative side is equally devastating, which results in compounding being required to even sustain an investor’s lifetime spending.

Inflation

The arithmetic makes it plain that inflation is a far more devastating tax than anything that has been enacted by our legislatures. The inflation tax has a fantastic ability to simply consume capital.

Warren Buffett

Inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services across the economy. The inflation rate measures how quickly prices are changing. The average inflation rate in Singapore was about 1.7% yearly from 2014-2024. So our hypothetical investor earning 5% p.a., is likely to have only ~3.24% p.a. real return on his investment.

Real return = investment return adjusted for inflation

Nominal return = investment return you see quoted in your account

Real returns formula

(A rough estimate is just to take Nominal return – Inflation rate)

An intuitive way to understand real returns is to think about it as the returns in today’s money. So for instance, our hypothetical investor ($10,000 growing at 5% p.a.) will have ~$16,200 after 10 years in nominal terms (in his account), but that money is worth only ~$13,800 in today’s money.

Inflation can easily sneak its way into our calculations on investment returns. Consider two examples:

- In the first, you buy a property in 2014 for $500,000 and that property is worth $800,000 in 2024.

- In the second, you also buy the property for $500,000 in 2014, but that property is only worth $550,000 in 2024.

| Example | Invested amount | Investment value after 10 years (nominal) | Investment value after 10 years (real) | Annualized returns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $500,000 | $800,000 | $675,900 | 3.06% p.a. |

| 2 | $500,000 | $550,000 | $464,700 | -0.73% p.a. |

While on paper it looked like you made money in both examples, in example 2 you actually lost money in real terms. This is because the spending power of $550,000 is less in 2024 compared to 2014. Also, even in the first example, what looked like a 160% return on investment (r.o.i), was really only ~135% real r.o.i.

Compound interest and inflation are not intuitive concepts for most people. Our brains are just not wired to do such calculations intuitively. We may have a good sense of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, but when it comes to compounded returns we tend to lose track of it. I can’t tell you off the top of my head how much difference it would make to change the annualized returns from 3% to 4% or to change the inflation rate from 1.7% to 2%. This is why investment, and financial goals in general, require careful thought and planning.

Retirement

Order 0 on retirement is to recognize that retirement is about providing a sustainable income in retirement, a standard of living, not a pot of money.

Robert C. Merton

How much do you need to retire? There are two ways you could answer this question: (a) a wealth number at the time of retirement, e.g. $500,000, or (b) your desired monthly expenses when you do retire, e.g. $2000/month. These are very different units of measurement and should be treated differently. By far the number that is more useful to us is the monthly expense. In order to retire, we need to be able to sustain our lifestyle across a long period of time; telling us we have $X in our account at only one point of time tells us nothing about how our lifestyle can be sustained. Furthermore, the conversion of wealth number to monthly spending is a very complex mathematical calculation (the reason it is complex is due to the previous two concepts we discussed earlier, compound interest and inflation).

Let’s take a look at a standard retirement period from 65-95 years old (30 year retirement). Suppose you have $500,000 in your retirement account at 65. In an ideal world with no inflation and no increase in account value, you can spend:

$500,000 / 30 / 12 = $1389 / month

This is probably only sufficient for a frugal lifestyle with no dependents in Singapore. Most young healthy students living with their parents can probably live with that much money, but as you age other expenses tend to pile up. Paying monthly bills, more frequent visits to the doctor, increased price of insurance, etc. Now when you add in inflation things get even worse.

$500,000 is already a pretty big sum to most of us, yet it seems barely sufficient to sustain an individual through retirement. Accounting for inflation, your chances of running out of money before you die becomes pretty high.

This is why it is important to invest. It allows us to use compound interest to build a larger amount of wealth to sustain us through retirement. As we shall see, there are also investments that can either keep up with or outpace inflation. This means our money would also be constantly growing even while inflation is happening. This greatly decreases the chance of running out of money.

But now if we consider inflation and compound interest (i.e. reality), converting our wealth number to desired monthly spending becomes very complicated. If your portfolio lost 10% this year, even if inflation is 0%, you might have to adjust your expenses. If your portfolio makes 0%, but there is 10% inflation this year, you also have to adjust your expenses. Both inflation and portfolio returns are not within your control, the only thing you can control is how much to withdraw and spend. I will go through retirement spending strategies in a different post, but my view is that this is one of the things in financial planning that is much better done with the help of a good financial advisor.

The 4% rule

Here I will just go through a simple concept popular in FIRE communities, which stands for Financial Independence, Retire Early. Commonly referred to as “the 4% rule”, it says that for a 30-year retirement period with a portfolio invested 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds, you can withdraw 4% of the portfolio in the first year of retirement, and increase the withdrawal amount by adjusting for inflation every year after, without running out of money. That’s pretty cool, let’s run through an example.

Suppose you have $500,000 and you invest it into a portfolio of 50% stocks, 50% bonds. Assuming 2% inflation, according to the 4% rule, you can withdraw:

| Year | Withdrawal amount (yearly) | Withdrawal amount (monthly) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | $20,000 | $1,667 |

| 1 | $20,400 | $1,700 |

| 2 | $20,808 | $1,734 |

| … | … | … |

You can immediately see the appeal of investing here. The $1,389/month you could spend before increased to $1,667/month in the first year and the impact of inflation is accounted for in every subsequent year. Perhaps more appealing to most people is the fact that you now have a formula to convert desired monthly spending to a wealth number, and vice versa:

$500,000 allows you to spend:

$500,000 x 4% / 12 = $1,667 / month in real terms

Working backwards, if you want to spend $2,000/month:

$2,000 x 12 / 4% = $600,000

You would need $600,000 in your retirement account to meet your spending goal. A popular way to extend the 4% rule is to extend the period of retirement. The thought is this: since you will not run out of money with the 4% rule, if you only require $2,000/month in your spending, you can retire once you hit $600,000 in your investment account. You don’t need to wait till 65, and you can be financially free from working much earlier in life. This thought has been extended by many in the various FIRE communities around the world. Many in this community aim to hit their “FIRE number” as early as possible (sometimes in their 30s even), which refers to the wealth number they need to sustain their desired monthly spending.

I think the 4% rule is an amazing concept. It simplifies complex retirement planning enough to bring it into the arms of laypeople. It allows people to make better financial plans for themselves, and it can give many people hope and something to look forward to in their dreary everyday work. If the 4% rule gets you to be motivated to work hard, plan finances carefully, and build the life you want, I strongly encourage you to stick with it. I leave an optional section here with discussion on the downsides of the 4% rule.

Downsides to the 4% rule

The 4% rule was developed by William Bengen using US market returns between 1926 and 1976, and was later backed by a further study referred to as the “Trinity study”. Perhaps the first problem with the rule is the way it has been extrapolated beyond the 30-year period studied. It may not be easy to see why extrapolation can be a problem if you are not familiar with investment returns. You might think: if my investment returns 5% p.a. and I only withdraw 4% yearly, I should never run out of money in theory right? Not quite. Investment returns can be very volatile, and more so for stocks over bonds. In a good year stocks may rise 30%, but it might also fall 30% the next. There may also be long periods of time where your investments don’t perform well. It may return -5% p.a. for a period of 5 years, but after 5 years return 10% p.a. But if you were to continuously withdraw 4% per year during that period, you end up taking on some risk that your portfolio runs out of money. This is called “sequence of returns risk”, where the order of your investment returns affects your portfolio longevity even when the average investment returns stays the same. Now the studies showed that this would not happen for the historical US data in a 30-year period. But if we were to extend the period to a 40, 50, or even 60 year period, the risks of running out of money increases.

The second problem with the rule is that it was based on US data. We now know today that the US stock market has had an exceptional run historically. Whether that great historical run will continue, nobody knows. But I think it is reasonable to take a more conservative estimate of expected stock returns, even if you only invest in the US market. What I present as follows will be using a model for allocating and withdrawing from an investment portfolio: https://tpawplanner.com/ developed by the amazing Ben Mathew, an Economist with a Ph.D. from University of Chicago. I tested a portfolio with $600,000 using a 4% withdrawal rate with a 50% stock, 50% bond portfolio. Here are my assumptions: an expected (real) return of 5.2% p.a. for stocks, and 2.4% p.a. for bonds. Here are the results:

We see here a 77% success rate given our assumptions above, i.e. a 23% chance of failure. This graph shows the portfolio balance. As you can see it starts from $600,000 and slowly declines as we reach 95. The dark blue line is the most likely outcome (50th percentile), so our median leftover amount is $269,784. The light blue cone shows the possible outcomes from the 95th percentile (where markets do really well) to the 5th percentile (where markets do really poorly). At the 5th percentile, we run out of money around 86. Now if we were to keep everything constant and run the withdrawals for 10 more years we get this:

The success rate drops to 58%, and at the 5th percentile we run out of money around 76. While this looks bad for our 4% rule, not all hope is lost. Many people do make sensible adjustments to their withdrawal rates, and it is more common to see numbers closer to a withdrawal rate of 3% to 3.5% for retirement planning today. Here is the result of a 3% withdrawal rate:

This is in line with more serious academic research, which finds a safe withdrawal rate closer to 3% or less. The downside is that you need to save more to hit your initial $2000/month goal. Now instead of $600,000 you will need $800,000.

The good news is that despite the downsides to the 4% rule, you don’t have to use it as your spending strategy, you have the choice to spend more or less. If you allow for flexible spending patterns, you can still spend a similar amount as dictated by the 4% rule with a much lower risk of running out of money. The planning for this is slightly more complex and deserves a post on its own, so I shall not discuss it here. In light of all this, the sensible way to use the 4% rule is to use it as an estimate for your required wealth number, and not as an actual spending strategy. But if you are estimating the wealth number for a period longer than 30 years, I still think it would be better to use 3% instead.

Now that you are given a useful formula for estimating the amount of money you need to retire, you will quickly realize that retirement costs a lot. Probably a lot more than you thought. In some sense it is likely one of the most expensive things you will ever have to buy. This is where investing comes in. By investing for retirement early, you have to save less overall because you let compound interest work its magic. This paradoxically frees you up to spend more during the later periods of life by not having to frantically cut spending to save for retirement.

Investing can also be used in general to put excess cash to work, allowing you to save for big ticket items like a house, car, or a big holiday. For instance, suppose you wish to save for a $100,000 down payment in 5 years. Just by saving this in different investment instruments you get:

| Saving vehicle | Required monthly savings |

|---|---|

| 0% yield savings account | $1,667 |

| 2% yield savings account | $1,586 |

| 4% yield bond | $1,508 |

How to calculate this yourself

Method 1: Use an online tool

Method 2: Use the PMT function on excel. =PMT(rate, number of payment periods, present value of loan, future value of loan). This is useful for calculating loan payments, but to calculate how much to save for a big purchase, simply set present value of loan = 0, and future value of loan = -(amount you wish to save).

Hopefully I have convinced you that investing and learning about investing is important. The question you are probably most frantic to ask is how should I invest? The problem with that question is that the answer will be different for each individual, and different for different financial goals you set. The good news is that there are still some useful general things that can be said. You should learn about a few of the most basic ways to invest, not because you should follow them, but because that allows you to understand what works, why they work, and how you should adapt it for your own situation.

What sensible investing looks like

There are a few important tenets of sensible investing that most lay investors (and arguably professional ones too) should follow:

- Buy and hold the market

- Diversification

- Keep fees low

- Stick with your portfolio

These tenets of investing are taken as common sense in the investing world, so much so that even hedge funds and alternative investments offer themselves as just ways to diversify, not replace investments that follow all these tenets. But these tenets are not very intuitive ideas for a lay person. So let’s try to unpack each of these in turn.

Buy and hold the market

Don’t look for the needle in the haystack. Just buy the haystack!

John C. Bogle

In 2008 the price of an Amazon share was ~USD 4 . Today the price is ~USD 228, a whopping 57x increase in just 17 years. That’s a 5600% increase, or 26.85% p.a. (nominal) returns. Even after accounting for inflation, that is an incredible return on investment. But to get those returns you would have to buy Amazon in 2008, when it was facing competition from big retailers like Walmart and Best Buy. You had to believe that buying its stock was better than buying the stock of other big established companies. Professional investors and hedge fund managers spend practically all of their time looking for the next Amazon. They do grueling analysis of financial statements, hire industry experts to teach them about new technologies, and analyze every piece of news that is relevant to a company’s stock price. As a lay investor you don’t need to do this. Today there are funds available that allow you to basically buy the stock of just about every single investable company. If you buy such products, you don’t have to worry about finding the next Amazon because you will already be holding it.

By simply learning that you can buy the entire stock market, you gain an important benchmark. Historically, investing in the US stock market (measured by returns on the S&P 500) returned ~10% p.a. in nominal terms from 1965 to 2024. Warren Buffett, who is one of the greatest stock pickers and investors of all time, has a record of ~19% p.a. over the same period. But even Buffett himself thinks that 99% of people should not attempt to pick individual stocks, and thinks most people will end up being better off having invested in the whole market. While there are a few exceptional individuals that can do better than the S&P 500, they are perhaps as rare if not more rare than finding the winning stocks themselves. Furthermore, the average investor will likely have no access to such exceptional individuals. Funds managed by genuinely skilled active investors tend to limit the number of assets they manage. This is because of economies of scale, where their winning strategy is unable to be scaled up without losing performance.

This argument extends to many actively managed funds as well. Some of these funds will just hold most of the market but sell you the promise of being able to weave in and out of the market to avoid negative downturns. This is all great when it actually works out, but on average it doesn’t. Again, to pick the winning funds you have to identify the funds that are successful before they show outstanding returns. You can’t just pick the funds that are already performing well, because these tend to counterintuitively perform worse in the future. An ongoing Persistence Scorecard by S&P finds that of the active funds that performed in the top-quartile in December 2020, not a single fund remained in the top quartile over the next four years. Moreover, these actively managed funds often cost a lot more in fees, sometimes taking up to 2% (or even 3%!) per year in fees. This means that even if the fund managed to beat the market, most of the excess returns likely went to the fund manager, not the investor.

The simple explanation for why it is so difficult to beat the market, is that future price movements are random. Whether the market goes up or down tomorrow, likely depends on tomorrow’s news more than anything else. Since new information (tomorrow’s news) is essentially random, the likelihood you make the right call for a trade is no better than even chance. It is thus hard to tell if the outperformance of any fund manager is due to skill or just dumb luck.

Diversification

Diversification is the only free lunch in investing.

Harry M. Markowitz

Typically in the investing world, you are unable to decrease risk without decreasing expected returns. Conversely, to gain more expected returns you have to increase your risk taken. But by diversifying across stocks that move independently and have similar expected returns, you can decrease risk while maintaining the same expected returns. This is why Markowitz calls diversification a “free lunch”.

An illustration of why diversification works (optional)

Suppose you are looking at two stocks, Stock A and Stock B. Stock A and Stock B both on average return 5% p.a. Since stocks are volatile, we try to capture that with a simple model: to decide on what Stock A returns, we flip a fair coin. If the coin lands heads, Stock A returns 6.5%. If the coin lands tails, Stock A returns 3.5%. In this case, if you buy Stock A, the standard deviation of your returns (an estimate of how far Stock A’s return can differ from the average) is 1.5%. Now let’s do something similar for Stock B. Stock B’s return is decided by another coin toss, which is independent from Stock A’s coin toss (i.e. whether Stock A’s coin toss lands heads/tail has no effect on Stock B’s coin toss). Just like Stock A, Stock B returns 6.5% if its coin lands heads and 3.5% if its coin lands tails.

Now here’s the neat part. If you just buy Stock A, you have an expected return of 5% and your returns have a standard deviation of 1.5%. But if you used the same amount you would use to buy Stock A to put half in Stock A and another half in Stock B, you would still have an expected return of 5%, but your returns would have a standard deviation of ~1.06%. Let’s look at how this works:

Option 1: Just buy Stock A

| Possible outcomes | Coin A lands heads | Coin A lands tails |

| Possible returns | 6.5% | 3.5% |

Mean = 5%, Standard deviation = 1.5%

Option 2: Half in Stock A, other half in Stock B

| Possible outcomes | Coin A heads + Coin B heads | Coin A heads + Coin B tails | Coin A tails + Coin B heads | Coin A tails + Coin B tails |

| Sum the returns | 6.5%/2 + 6.5%/2 | 6.5%/2 + 3.5%/2 | 3.5%/2 + 6.5%/2 | 3.5%/2 + 3.5%/2 |

| Possible returns | = 6.5% | = 5% | = 5% | = 3.5% |

Mean = 5%, Standard deviation = ~1.06%

As you can see, if you buy both Stock A and Stock B, there are more outcomes where your returns are closer to the average. Put another way, while your expected return for buying Stock A vs both Stock A and B are the same, you are more likely to get an actual return closer to your expected return by buying both stocks.

A note on risk (optional)

Here I am using risk interchangeably with standard deviation. Standard deviation is a measure of how far data points are from the mean. An intuitive way to understand standard deviation, is the range of returns you could get for buying an asset. For example, if your range of returns is from -30% to 30% the risk (standard deviation) is quite high. If the range of returns is from -5% to 5% the risk is quite low.

Risk is understood as standard deviation in very local contexts where all you care about is portfolio returns. But this is not the only or even the best understanding of “risk”. A perhaps more important definition of risk is the likelihood of running out of money when you need it. If this is the case, you might want a higher standard deviation (more “volatility risk”) if the higher standard deviation is required to get you enough money when you need it (e.g. to outpace inflation). This concept is perhaps more relevant when considering retirement planning, so I have omitted it from the main text.

Diversification goes beyond simply holding two different stocks. You can diversify across asset classes—stocks, bonds, cash—and across industries, countries, risk factors, fund managers, and more.

Now in the real world, many of the assets you will buy are not independent from each other. But to get a diversification benefit you don’t need independence per se. Instead, you need two things: (1) the assets must not be perfectly correlated with each other, and (2) the assets have similar expected returns. Both (1) and (2) come in a range; assets could be more or less correlated and more or less similar in expected returns to each other. The less correlated they are, the better the diversification benefit. Conversely, the more correlated they are, the less benefit from diversification. The reason for this is quite intuitive, if you have two stocks that move together, e.g., their returns follow the same coin flip, that would be the same as just buying one of the stock.

On the other hand, when expected returns are less similar, if you add a lower expected return asset it pulls down the expected returns. If instead you add a higher expected return asset it pulls up the expected returns. However, if you add in an asset with lower expected returns but with very low or even negative correlation with your other assets, this may lower the volatility of your portfolio greatly without decreasing expected returns by much (bonds come to mind here).

Sharp readers will have noticed that by buying the market, you automatically get some diversification benefit. So this further reinforces the idea that buying the market is a sensible way to invest. However, sometimes people mean different things by “buying the market”. Some think buying just US stocks count as “buying the market”, others think it has to be international stocks too, still others think you need bonds, etc. Instead of being too caught up in what “owning the market” means, I think it is better to understand how diversification works, and to decide how you yourself would want to diversify in your portfolio.

Keep fees low

We investors as a group not only don’t get what we pay for, we get precisely what we don’t pay for. So if we pay for nothing, we get everything.

John C. Bogle

Those new to investing will find the emphasis on low fees counterintuitive. Most of the time when we pay more money, we get better stuff. If I spend $100 more on a phone, I can expect some better features like storage, battery life, camera quality, etc. In investing it is often the opposite, the more you have to pay the worse of a product you get. This puzzling feature comes about because of the difficulty in beating the benchmark market returns. On the one hand, it is super simple and cheap to just buy a fund that owns the whole market. On the other hand, to beat the market returns you need to spend money hiring really smart people who graduated from top schools. You then put them in a very chaotic environment where they periodically get rewarded for skill but mostly get rewarded/punished by luck. To top it off, many of these smart people are fighting tooth and nail over every extra cent that can be squeezed out of pricing discrepancies in the market, so there isn’t a lot to go around. It will thus be incredibly rare to find funds that have higher fees, but still manage to give the investor even higher returns on top of those higher fees.

Investment fees can be quite difficult to understand as a beginner. A general rule of thumb is that the more you trade, the more you pay in fees. This is another reason why active funds tend to perform worse, they incur more fees. I think it will be useful to highlight the major ones:

- Total expense ratio (TER)

- Dividend withholding tax

- Capital gains tax

- Estate/legacy tax

- Brokerage transaction fees

- Foreign exchange/FX fees

- Advisor fees

There are probably more possible sources of fees, but I highlight the most common ones investors will incur. Let’s go through them one by one.

Total expense ratio (TER)

This is how much you will pay annually to the fund managers for owning their fund. You can often find this on a fund’s factsheet or its website. Here is an example using iShare’s fund that tracks the S&P 500 (CSPX):

As you can see, CSPX has a TER of 0.07%. That is the percentage of the money you have invested with them that you will have to pay yearly. Needless to say, whenever you wish to buy a fund you should shop around for similar funds and compare their TER.

To get a sense of how much you can save, a $100,000 investment in an actively managed mutual fund with 1% TER will cost you $970 more compared to buying CSPX in just the first year alone. As we have learnt from compound interest, you actually lose even more next year, since you have $970 less to compound on the following year, and so on for the next next year, etc.

It will also be useful to learn to calculate the TER of your portfolio as a whole. To do this we need the weighted TER, calculated by the following:

weighted TER = (% allocated to asset A x TER of asset A) + (% allocated to asset B x TER of asset B) + …

Here is an example. Suppose your portfolio is 60% in CSPX, and 40% in iShares Global Aggregate Bonds (AGGU). AGGU has a TER of 0.10%, so you calculate your weighted TER as follows:

weighted TER = (60% x 0.07%) + (40% x 0.10%) = 0.082%

While TER is quite important, you don’t have to go too far in chasing the cheapest option possible. Dropping your TER from 1% to <0.3% is pretty huge. But dropping it from 0.3% to 0.25% is a lot less of a hit to your financial goals. If for whatever reason you want to hold a slightly more expensive fund, e.g., you are very confident in the fund manager/company, then I think you should go ahead if it helps you stick with that portfolio.

Dividend withholding tax

All information about taxes assume you are taxed as a Singapore tax resident. Since tax regulations can and do change over time, the optimal tax strategy likely changes over time.

Dividend withholding tax is simply tax you pay when a company pays out dividends to its shareholders. Dividends are a percentage of the company’s profits. If the company does better, they might pay more dividends. They might also just pay more dividends to try to boost shareholder confidence. Either way, some of it will be taxed by the time it gets to you.

Most of the funds that you hold will buy shares of US companies. They will thus be subjected to US dividend withholding tax, and potentially your own country’s withholding tax. Note that all US stocks are subject to US dividend withholding tax. US stocks tend to find their way into most common ways of buying the market (both US and International), so this likely applies to just about every investor.

In general, US taxes 30% on dividends, and Singapore does not tax dividends. So you will face a 30% + 0% = 30% tax on dividends you receive. You do not need to file anything for this, since it is automatically deducted at the fund level.

There is a way to legally pay less of this tax. If you just buy from the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), you have to pay 30% withholding tax since the ETF is listed on a US stock exchange. If you instead buy from a fund that is domiciled in Ireland, commonly found on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), you can pay less tax. The US has a tax-treaty with Ireland, so the funds domiciled there only pay 15% withholding tax. At the end of the day, just by choosing to buy from a fund domiciled in Ireland instead of US, you save 15% on your dividend withholding tax. This is why many favor brokers that let them buy from LSE. The broker I am familiar with that has access to LSE is Interactive Brokers (IBKR).

Additionally, according to FSMone fixed-income ETFs domiciled in Ireland pay 0% dividend withholding tax.

Do note that US stocks and ETFs (like the S&P 500) listed on the Singapore Exchange (SGX) get a 30% withholding tax because Singapore has no tax treaty with the US. So buying US stocks on Ireland-domiciled funds is still better than buying them on SGX.

Capital gains tax

Surprisingly, we don’t have to worry about capital gains tax. US does not tax nonresidents capital gains tax, and Singapore does not tax capital gains either. Things could very well change though.

Estate/legacy tax

There is also estate tax which you have to pay to the US if you bought from US-listed ETFs on the NYSE. The first $60,000 is exempt, but the rest could be taxed as high as 40%. This can also be avoided by buying an Ireland-domiciled fund.

Brokerage fees

Each brokerage will have different fees, and different fee structures. Most have reasonably low commission fees because that is the one investors are most sensitive to. But because brokers find creative ways to make money, zero commission fees does not necessarily mean zero fees. Some brokers have a Payment for Order Flow (PFOF) system, where they are paid by market makers to route a trade you put to them. So let’s say you want to buy 5 Apple shares. They will route your trade to a specific market maker. The market maker is someone who is buying and selling stocks to provide liquidity in the market—they profit off the “bid-ask” spread, i.e. the difference in sell price and buy price. In some cases, this can be quite bad for the investor, since they might not get the best possible price when they send in their order. While there are regulations for market makers and brokers using this PFOF system, there are still brokerages that have been found to incur excess costs on their customers from this system. The result is that even though the customer pays zero commission to the broker, they end up “paying” more by getting a worse price during their trades.

What can we do about this? Not too much really. Its just a reminder that there is no (other) free lunch in this world. Brokers have to make money somehow, and they will always be making money off you. Shop around different brokers, and try to find more reputable ones. Don’t get hooked into shiny deals that brokers offer you. Find a broker you think is offering a reasonable price and service with good reviews. I personally use IBKR, and use the IBKR Pro – Tiered pricing structure.

Foreign Exchange/FX Fees

These are fees to convert currencies. It will be incurred quite frequently if you buy stocks or ETFs that are traded in USD. Some brokers have worse FX rates (another way they earn off you), again this is a comparison between brokers thing. I will just note that some might recommend manually converting currency from SGD to USD (or vice versa) instead of using the AutoFX conversion feature. IBKR Pro charges 0.03% on the AutoFX conversion, which I don’t think is too bad for the convenience.

Advisor fees

Here I include both robo-advisors and human-advisors. Both tend to charge a fee for assets under management (AUM). This functions effectively like the TER on your portfolio. The lowest I have found is a robo-advisor charging 0.3% yearly. For Endowus this is only accessible if you make your own portfolio (Fund Smart) and select only a single fund. If you instead invest in multiple funds you may be charged up to 0.6%:

Note: SRS and CPF-OA investments get better pricing.

I think it is perfectly reasonable for you to use a robo-advisor. It takes away a lot of the fuss from investing, and at the very least you have some control over what to invest in. I still think you should make your own portfolio, because some recommendations may not be in your best interest. You may also end up with a portfolio that doesn’t suit your needs. Just because you said you have X amount of risk tolerance doesn’t automatically mean you should invest in a certain kind of portfolio. Also, I would avoid funds that heavily focus into specific industries (like technology, or AI, or whatever). Think about what the tenets of investing say about such funds.

Some firms in Singapore also provide fee-only advisory. This is a big step up from commission-based advice, since there is less risk of conflict of interest. I believe market rates should be around ~0.8% yearly, which includes pretty comprehensive advice on financial planning. I also believe there is a minimum net worth to access the service (I have never used such services, so my info here could be wrong). For some this can be a really useful way to get good financial advice. There should also be some advisors that provide hourly fee service for financial planning. A good rule of thumb is to ask your advisor how they are compensated. Being compensated by earning a commission off the products they sell you is often a red flag. Good quality financial advice is very valuable, it is like going to a doctor for a health checkup. Unfortunately, the way the system works now, such advice is not widely available to those who need it the most. Do search around and look for reviews before utilizing such services. If anything, learning about the basics of investing from here should shield you against the worse case scenarios. If you do use such services some internationally recognized credentials could be a good thing to look for:

Certified Financial Planner (CFP): Requires passing exams on financial planning, taxes, insurance, estate planning, and retirement.

Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA): Requires passing exams on portfolio management and financial analysis.

Perhaps a general point that should be emphasized about fees again, is to not go too far chasing for the lowest fees. It can be very mentally exhausting for relatively little reward. Sometimes making things easy and smooth for yourself helps you to remove psychological barriers to investing. This is extremely valuable. The most important thing that affects your returns is still whether you actually invest or not. If worrying and fussing about different products, brokers, fees, make you delay or not want to invest, then you are probably better off just eating some excess fees and investing instead. At the end of the day, if you can get ~1% fees all things considered, you would be totally fine.

Stick with your portfolio

The most important thing about an investment philosophy is that you have one you can stick with.

David Booth

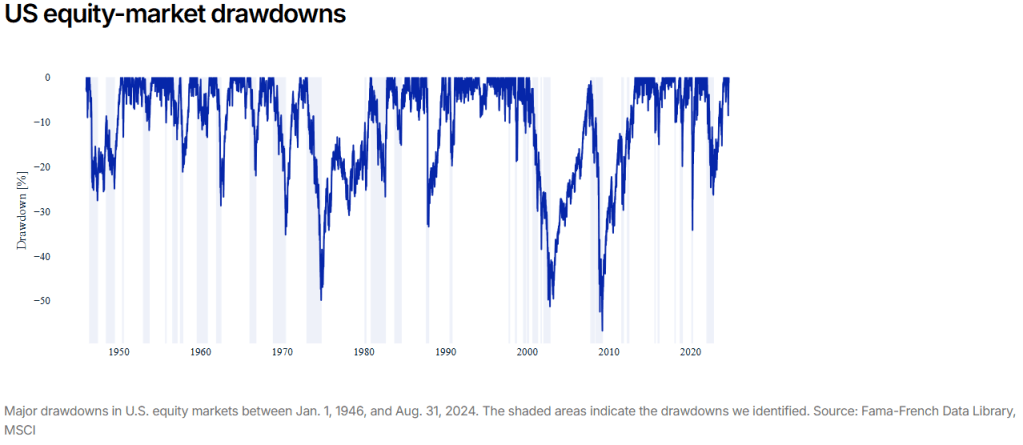

All investment portfolios will have draw downs over an investor’s lifetime. From 1900-2025, there have been easily 10 major market downturns/crashes, and probably more depending on how you count. In each downturn investors would take 10%, 20%, 30%, or even more, declines in their portfolio value. If you are investing in any kind of risky asset, you should expect these draw downs in your investment lifetime.

Despite, there being such draw downs, those who have typically stuck with their portfolios—not sell during these crashes—have come out net positive by quite significant margins. This is not surprising because they would have just taken the market returns, which we saw was ~10% p.a. (nominal). It is really only by sticking with your portfolio through thick and thin, will you be able to accrue the high expected returns of risky assets.

This is why it is so important to know, understand, and be comfortable with the portfolio you have. As Benjamin Graham says “The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself”. If you find yourself anxious, stressing out, and unable to sleep every time you see some decline in your portfolio, you should seriously reconsider the amount of risk you are taking.

One thing that is underappreciated by most investors (even the informed ones!) is that risk is real. You can lose money on your investments. Some investors think stocks just have short term volatility. They think if you can put money in stocks for a really long time you are guaranteed returns near the average. That’s not how investment, or math works. There is still a wide spread of possible results from stock returns in the long term, even if the annualized returns converge to the expected returns. The spread tends to be even wider for riskier assets, and you are certainly not guaranteed the average returns.

Before choosing an investment portfolio, you should really ask yourself how much you are willing to lose. The more you are willing to lose, the higher the expected gain. Without taking more risk, you can’t get more returns. If you find yourself holding back from investing because you are scared of a coming market crash, this is a signal that the portfolio is too risky for you.

In a different post I will go through Choosing an investment portfolio. In there I explore both standard portfolio combinations, and portfolio combinations you can make on your own. Do note that being part of a community that can rally together and stick through the same investment through good and bad times can help you to stick with that portfolio. This may be a point for or against making your own portfolio depending on how much you engage with these communities.

Putting everything together

There may be good reasons to deviate from the basic tenets of investing: Buy and hold the market, Diversify, Keep fees low, and Stick with your portfolio. But importantly, you must have good reasons. They shouldn’t be made on a hunch or a whim or a speculation of what is going to happen in the next 6 months. An example of a good reason is that you would not invest if it was too much of an annoyance, so you pay an advisor to do it for you. An example of a bad reason is that you heard PM Wong say the economic times ahead are difficult, so you sell out parts of your portfolio waiting for a dip.

We have went through quite a lot at this point. If you made it this far, good job! Give yourself a pat on the back and grab a small snack—you deserve it.

So far you have learned about why learning about investing is important, the basic concepts in investing, and what characterizes sensible investing. Let us put everything together with a few concrete examples.

Example 1: Investment-linked Policies (ILPs)

An agent comes up to you and offers you an investment opportunity. They tell you that you can put your excess money to work by buying one of their company’s investment products. They even tell you about investing in a large basket of stocks, adjust their recommendation based on how much risk you are willing to take, and appear to be genuinely listening to you and taking your personal situation into consideration.

Here is the opportunity they offer you:

You get to invest in a basket of US stocks and even switch between different funds. The fund has been performing quite well over time, about 8% p.a. On average you can still expect to earn about 4% p.a., but if things go well you can earn 8%, or even 12% p.a. The product is technically an insurance, but it puts 100% of your money into investments so no money is lost by paying for insurance premiums. The drawback is that once you put in your money, you cannot take it out for the next 10 years. If you wish to do so, you will likely incur net losses. Should you invest with the agent?

What you should realize is that the details I provided don’t give you enough information to make a decision. You should follow up by asking things like: what are the fees I have to pay? what other services do you provide? how much money could I potentially lose?

Let us suppose they charge a 1% yearly fee total, with no added charges. You should then consider how the 1% yearly fee adds value to a product you could buy from a broker or robo-advisor for less. Can this agent help me with other important financial planning matters? Will they help me to navigate difficult topics like taxes, retirement planning, estate planning, and insurance coverage? How can they help me during times when I feel very insecure about the market? Can they keep me grounded and give me rational advice when there is a new hype opportunity? Does my beliefs about investment line up well with them? How well can I understand their explanations about financial planning? By asking these questions, you can find out if this agent is right for you.

If you find that the agent is very helpful and adds a lot of value to your situation, you should then consider the fund they are selling you. Does the fund follow the few basic tenets of investing? Let’s go through them:

- It owns a basket of US stocks, but when you ask more about the details they tell you the fund manager dips in and out of holding the stocks, or choose to actively pick “winning stocks”. You know that this is a very difficult game to win, and so you should ask if there are different funds that can just buy and hold the market passively.

- The stocks are also not as well-diversified as you would like, since they only hold US stocks, while you might prefer holding international ones. Perhaps you also want some bonds in your portfolio because you wish to reduce the potential losses on your capital.

- The fees are pretty high, on sum still around 1% which might not be too egregious. But you note that this drags down on your expected returns.

- You find out that you mostly will be holding stocks, and you might face real losses of up to 50%. You think to yourself that the 4% average returns might not be so great given the risk you would have to take. You would rather add in some bonds to decrease the maximum drawdowns. You do note that you will almost definitely stick with the portfolio because you don’t want to incur losses by surrendering the policy early.

I hope this example helps to work through some of the main things you should think about when deciding on an investment product. At many points you may choose to avoid the product because there is a deal-breaker response you cannot accept. But some might actually end up with an arrangement they are happy with. You should get to decide whether this works for you or not, and not let some internet person (or anyone else) make a choice that has great impact on your life for you.

Example 2: VWRA Baby!

Your good friend tells you to just buy this thing called VWRA:

It is a total market cap-weighted index fund by Vanguard. It is listed on the London Stock Exchange, and has a TER of 0.19%. Your friend tells you that they just buy 100% into this ETF and nothing else, and encourages you to do the same. Should you follow their investment strategy?

Let’s assess this fund in the same way as before, with the basic tenets of investing:

- It owns a basket of International stocks. The fund tracks a world index and is passively managed, so the fund manager just algorithmically follows what the index says. There is no attempt to time the market or pick individual stocks.

- It is well diversified across geographies, basically every country that you could invest in falls inside the index fund. It has no bond component, which you might want to reduce the potential losses on your capital.

- The fees are quite low. You know that CSPX has even lower fees, but since CSPX only invests in the US market it may be worth the extra fees to get international diversification.

- You are quite happy with the performance of the fund, as it returns ~11% p.a. You do note that stocks in general could see quite significant draw downs and also wonder whether you can accept the potential for real losses of up to 50%. Since you worry about this, you also hesitate with how much you are willing to save into the investment.

In general, most people will recommend you to buy something like VWRA. It is a good product, a sensible way to invest, and hits most of our tenets of investing. But you might not want a portfolio consisting of 100% VWRA, since that would make your portfolio entirely stocks. You should think about how comfortable you are consistently putting your savings (essentially your life savings) into an asset that fluctuates so wildly with a real potential of significant losses. I personally hold a 100% stock portfolio, but it is not clear that everyone should be holding one even if they have a long investing horizon.

The end!

If you made it all the way, you would realize that total market cap-weighted index funds are good investment products. They buy and hold the market, are well diversified, and have extremely low costs. But no matter how good the product, it doesn’t matter if you cannot stick with it and regularly invest into it.

I would also like to emphasize that index fund investing is not inherently good. It is good because it fulfils all the basic tenets of investing. Index funds that do not fulfil these tenets can be bad products. Conversely, non-index funds investments that fulfil these tenets can be good. You are now well-equipped to scrutinize the different investments you are offered, the investing world is your oyster. Want to add some uncorrelated asset to improve diversification for your index fund portfolio? Go ahead. Want to capture more of the overall market by owning bits of private equity? Sure. Want to optimize for the lowest fee portfolio possible? All power to you. Want to keep things as dumb and simple as possible? Great. As long as you have a sensible portfolio you can stick with, things will probably work out well for you.

Hopefully this guide has helped you to take a step into the world of investing. I recommend continuing the learning journey: look for books, go for financial literacy talks, and check out youtube videos. Don’t spend your time watching your portfolio, following every market movement, or jumping on the next hype product. Use your time to learn and improve your financial literacy instead. If you have any feedback or questions, please let me know. Thank you for reading and hope you enjoyed it!

Read next: Choosing an investment portfolio or How much should you save?